Make The Grammys Great Again

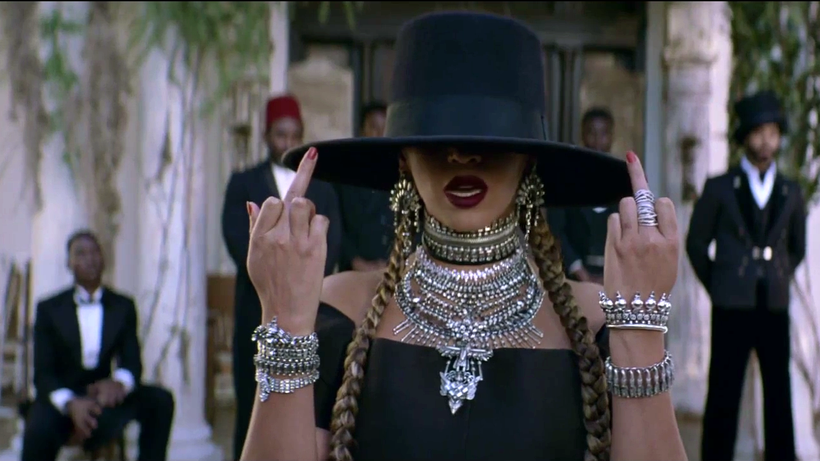

We all got some serious deja vu when Adele was graced with the Album of the Year Grammy award and melted into a tearful speech about why Beyoncé should have won instead.

“Beyoncé should have won.” How many times have we heard this now? There was the infamous 2009 VMAs where Kanye West snatched the mic from Taylor Swift. Then there was the 2014 Grammys when Kanye, upset by the Grammys’ persistent snubbing of black music, took a misguided stab at Beck. And it’s not just Beyoncé. The same year Beck’s Morning Phase won, Macklemore won in three of four rap categories, beating out Kendrick Lamar’s good kid, m.A.A.d city. A serious conversation about race and the Grammys began, and after Beyoncé lost to Adele this year, #grammyssowhite started trending on Twitter.

Neil Portnow, president of the Recording Academy, denied that the Grammys have a race problem, pointing to Chance the Rapper’s win in the Best New Artist category. “You don’t get Chance the Rapper as the Best New Artist of the year if you have a membership that isn’t diverse and isn’t open-minded and isn’t really listening to the music, and not really considering other elements beyond how great the music is,” he claimed.

Plus, Bey won “Best Urban Contemporary Album” for Lemonade in addition to “Best Music Video” for “Formation”, so no problem, right?

Well….

WTF Is “Urban Contemporary Music”?

First, a refresher in “urban” as a euphemism for “black”:

When 6 million African Americans from the rural South migrated to the urban north in the 20th century, white people started leaving for the suburbs. Some cities saw absolutely massive demographic shifts: by the 70s, 80% of black people lived in cities, while Detroit lost more than a quarter of its white population, Cleveland lost about 20%, and Chicago about 15%. In this context, “urban” as “black” actually makes some sense.

“Urban contemporary”as a label for “black music” was actually coined in the mid-70s by a black DJ—New York City’s Frankie Crocker—who wanted to label and market the genre-crossing mix of songs he was playing for his mostly-black NYC radio audience. His multi-genre format turned out to be a hugely successful recipe, even for white listeners. WBLS-FM (Crocker’s station from 4-8pm) was catapulted to the number 1 slot for young listeners in NYC. Commercials started advertising for products that weren’t traditionally marketed to black people. Asked what his radio format was, Crocker simply said, “it’s what’s happening in the city.”

Fast forward 40 years, and now there’s a Grammy category by the same name, created in 2013 by nonwhite R&B producer Ivan Barias for albums with “newly recorded contemporary vocal tracks derivative of R&B.” Potential nominees would include “artists whose music includes the more contemporary elements of R&B and may incorporate production elements found in urban pop, urban Euro-pop, urban rock, and urban alternative.”

Barias felt the “really inclusive category” was needed to celebrate “artists who tend to pull from different genres; for example, there’s a lot of albums in that category that contain elements of R&B, hip-hop, pop, rock, and electronic dance music.” Rather than being a smaller category, Barias insists that it shows “how expansive and critical our music culture is right now in the urban genre” by being inclusive to to the “amalgamation of sounds” that artists like Beyoncé or Rihanna demonstrate.

In other words, the “urban contemporary” label was started by non-white guys and is supposed to mean eclectic. You can’t cram Beyoncé into R&B, and you shouldn’t try, so it’s only fair to give her her own category. Give “urban” artists their own platform, promote inclusivity…done?

No Racism, No Problem

Not so fast. Because now we’re seeing a bit of the reverse of the 20th century, with black people moving in large numbers into the suburbs, and white people moving into inner cities. In fact, Detroit and Chicago are now two of the cities seeing the biggest black population decrease. And I shouldn’t have to say any of that to make it clear that “urban” just means “city” and “city” doesn’t mean “black.”

But only black people even been nominated in the Urban Contemporary Music category since its conception. And only 10 black people have ever won Album of the Year, and the last one was Herbie Hancock in 2008 for an album of Joni Mitchell covers.

We only have a few options here:

1. Cop to “urban” as an acceptable synonym for “black”, decide that segregating the Grammys is a-OK, and accept this hilarious Wikipedia edit as an actual fact

2. Blame “black music” for not coming up with its own award shows of equal cultural weight

3. Decide that only 10 black musicians have ever been worthy of a Grammy in a major category since 1959.

4. Admit there’s a race problem, figure out why, and fix it.

Structural Racism: Who’s The Judge?

“The new racism exists without racists … Today, racial segregation and division often result from habits, policies, and institutions that are not explicitly designed to discriminate. Contrary to popular belief, discrimination or segregation do not require animus. They thrive even in the absence of prejudice or ill will. It’s common to have racism without racists … the new racism is disconnected’.

Eduardo Bonilla-Silva

People have a knee-jerk defensive reaction to the word “racism”. Some people think racism means the n-word and swastika graffiti, Jim Crow and apartheid. But structural racism is actually way more subtle than that. The people who perpetuate it are usually well meaning folks who probably aren’t “traditionally racist” at all. They just don’t see how “traditional values” and “the way we’ve always done things” perpetuate inequality. They don’t understand that you don’t even have to dislike someone to accidentally participate in discrimination.

Last year, Billboard interviewed a pair of Grammy voters about the voting process. One, a 30-something male R&B and pop producer, claimed that “the voting bloc is still too white, too old and too male.” He said that he sees a significant difference from three or four years ago, as “the voters are becoming more diverse in terms of minorities, females and younger ages — but there’s still a long way to go.”

Meanwhile, in the first of two rounds of voting, people can vote for nominees in categories that they know absolutely nothing about, leading to already-famous people amassing more votes because of visibility. Then, a separate, secret committee votes on the final nominees and winners, and can even override the decisions of the first panel.

So: old white dudes voting on categories they don’t know much about in secret. That’s our recipe for diversity and inclusion?

Who’s The Audience?

To recap: the Grammys are one big, secret voting booth of old white dudes, and then we’re all surprised that Beyoncé doesn’t win for Lemonade. Why would we expect a voter panel that looks and works this way to select Lemonade, about the experience of black motherhood and black southern womanhood? Or To Pimp A Butterfly, racially and politically charged, or even good kid, m.A.A.d city whose more mainstream production only sort of paints over its slightly-less-racially-explicit content that discusses gang violence and substance abuse. These themes are enormous, they’re terrifying and essential and unapproachable.

Then we’ve got Macklemore, whose “Thrift Shop” ended up on the Billboard top 10, and who won Best Rap Album. And Adele, who has an achingly beautiful voice, but whose 25 didn’t make any waves or break any walls.

Why on earth would Lemonade, Beyoncé, good kid, m.A.A.d city, or “To Pimp A Butterfly win in that context? With those voters? Against safer, less political rivals?

Those albums in many ways are not “for” white audiences. And that’s okay—God knows everything else is. And saying that Beyoncé or Kendrick Lamar didn’t win Album of the Year because they’re black artists with black albums for black audiences is not the same as saying that they lost because they’re black. I sincerely doubt that there are very many Grammy voters consciously including race in their criteria. But that’s also not the same as saying that race doesn’t play a role.

What we can’t do is continue to claim there isn’t a race problem at the Grammys if we’re going to deflect some of this generation’s most culturally important artists to the sidelines. Is Best Urban Contemporary Album part of the solution, or is it a mainstream-approved makeover of the same old problems?