Marriage equality can be romantic, but it’s mostly practical

On Friday June 26, 2015, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled 5-4 to legalize same-sex marriage nationwide. The victory is a historical milestone that will rapidly enter into the Civil Rights Section of American history textbooks.

The fight itself has lasted decades, and victory has been a long time coming for its tireless activists, many of whom have been systematically denied freedom of sexual and romantic expression. In truth, though, for many prospective gay brides and grooms the issue is less romantic than it is legal, practical, or financial.

Denying an autonomous adult the right to marry chips away at basic humanity and revokes rights of citizenship, but love exists without marriage and indeed had for many years before the fight for marriage equality launched wholeheartedly. Somewhere around the 1980s, it became clear to everyone that the issue of same-sex marriage was about much more than love.

Choosing Battles

In the 1940s all the way through the 1970s, same sex marriage was an improbable and almost inconceivable idea. It simply wasn’t a priority because LGBT activists (a term coined only recently) had so much more to worry about. People were actively discriminated against at home, at work, and in the street. Parents were disowning their gay children; homosexual men and women were fired from jobs or otherwise couldn’t get them. Being gay was literally criminal in most states. Cops raided gay bars and queer people were attacked, harassed, or threatened.

In the midst of all that hatred, achieving marriage equality would have been laughable. It was enough just to love freely and live in peace. In fact, it wasn’t even until 1973 that states, beginning with Maryland, began writing laws explicitly prohibiting same-sex marriage.

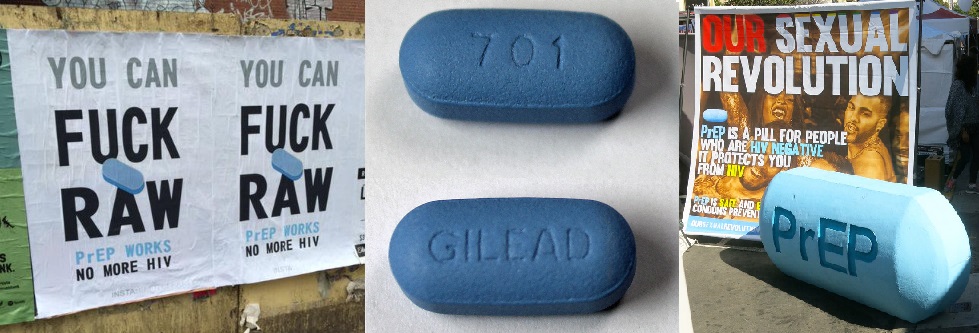

In the 198s the AIDS epidemic struck, around which time lesbians began having children together by means of donors or artificial insemination at a rate so huge and sudden the era became known as the “lesbian baby boom.” Parents, lovers, and activists began to realize that marriage was not just a romantic ideal, not merely a government stamp of approval of your relationship. There was a fundamental and extremely important right being denied here. A new battle emerged.

Marriage Is Security

My younger self said it all the time: “I don’t need to get married; I don’t need a piece of paper to confirm my love.” My then-married parents–receiving both financial and medical benefits due to their union–told me I’d understand when I was older.

My younger self was right, in a way. You don’t need a piece of paper to confirm love: you need it for tax and social security benefits; visitation rights, treatment consultation and medical insurance; legal guardian or surviving spouse status. You need it for financial and legal security. Two people, when married, are elevated in the eyes of the law to a superior union, a cohesive legal unit. Denying a couple of any orientation those rights is a far more tangible evil than the abstract “freedom to love.”

Taxes

Until the SCOTUS ruling, married but unrecognized couples had to file as “single” on tax returns (rather than “married” which can pull couples into lower tax brackets). Unlike legally married couples, same-sex couples also had to pay taxes on property transfers like real estate or bank accounts as though they were income—whether the individual is “gifting” the property or leaving it in a will.

Social Security

Only the spouses of deceased individuals can collect social security payments. Those payments increase greatly if the surviving spouse is taking care of the deceased person’s child. This is often the only form of income for an older single spouse, which is okay because collections can be as high as $30,000 per year. Same-sex couples who live in states that do not recognize their marriage are not entitled to their dead spouse’s social security, and receive no financial compensation for childcare because they are legally of no relation.

Medical Care

It is in the category of medical care that same-sex marriage acquires the most urgency.

If a marriage is not legally recognized, one spouse cannot be covered under the others’ health insurance. This becomes an even bigger problem when there is a child involved—if the birth parent does not have her own medical insurance, neither she nor the child is covered. The health coverage that comes with marriage grows crucial when children are involved, as in the lesbian baby boom.

Further, unrecognized spouses of sick or dying people have no privilege in the eyes of the law, which means that gay husbands and wives are denied visitation, consultation in treatment, or surviving spouse status on death certificates and for inheritance and estate purposes. During the AIDS epidemic, widespread and systematic denial of these rights became an palpable outrage: so many partners of so many sick and dying people demanded to be treated as the spouses that they were. Quality of life depended on it.

Legal Equality

Unfortunately, federal approval of same-sex marriage will not eliminate discrimination. Marriage equality may not mean social equality. But marriage equality will now tangibly improve the quality of life for millions of humans, who had no problem loving before and now can live a little easier.

Legal recognition is, in many ways, more important than spiritual or romantic recognition. Love can exist and flourish under any legislative system, with or without the recognition. But making life as easy, providing the same protection, security, and benefits for same-sex couples as straight ones—that’s irreplaceable. That’s necessary. Humanity demands it.

Love won this Friday, won something even more practical than love.