Is Truvada the beginning of an answer to the AIDS crisis?

The newest tool in the battle against HIV/AIDS has just entered the global playing field. Truvada is the first FDA-approved HIV prevention drug. It has been used in conjunction with other medications to treat diagnosed HIV for years, but was approved as a preventative medication in 2012.

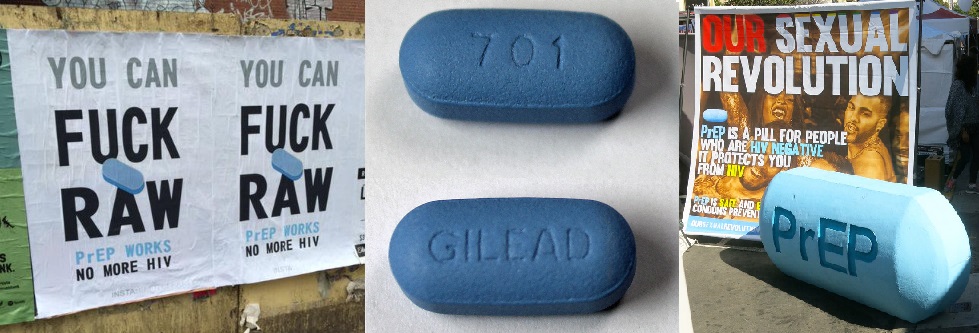

A quiet ad campaign has been launched in the last year, promoting itself primarily to HIV negative people in (primarily homosexual) relationships with HIV positive partners. You might have seen ads for PEP or PrEP (Post-Exposure Prophylaxis and Preventative-Exposure Prophylaxis), like the ones below, on bus stops in NYC and elsewhere. Take one PrEP pill every day to remain HIV negative, regardless of your partner’s status. Take one PEP pill a day for three months after exposure or potential exposure to HIV.

A drug like this can change the face of the gay community at the very least, make drug users safer, and eradicate a global health crisis at best. It sounds too good to be true. But is it?

The Potential

The rate of HIV and HIV contraction may be down since its peak in the 1980s, but it’s been on the rise in the 00s among young gay men. In 2010, gay men accounted for 63% of all new HIV infections, and saw a massive 12% increase in annual new infections between 2008 and 2010. Younger gay men account for almost 20% of all new HIV infections, and that rate increased by 22% between 2008 and 2010. Altogether, about 1 in 5 gay men are living with HIV nationwide.

Add to this the fact that 13% of HIV positive people don’t know they’re positive, and you have a recipe for disaster. For any high-risk young person, a preventative medication like PrEP could be the difference between life and death—or joy and anxiety—in a casual one-night stand, or when sharing regular relations with a partner.

This, of course, is just in the United States. Truvada has the potential to save millions of lives across the world. 70% of all people living with HIV live in Sub-Saharan Africa, and the HIV contraction and AIDS death rates are increasing in the Middle East and North Africa—though they are declining elsewhere.

With so much at stake, does it work?

Kaiser Permanente, the largest San Francisco health insurer, performed a two-year study of 657 high-risk clients, published in Clinical Infectious Diseases. Not a single one of their clients receiving Truvada became infected over a period of more than two years.

The Cost

Truvada’s manufacturer, Gilead, reviewed records from about half of US pharmacies that dispensed Truvada between January 1, 2012 and March 31, 2014 and found that only 3,253 people had started the PrEP regimen during that period.

With over a million people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States alone, such dismal numbers are partly due to cost, which can be a huge obstacle preventing many at-risk people from getting on Truvada. It can be covered by insurance, but it costs around $1300 per month for uninsured people. Gilead does offer financial assistance, but copays vary, rendering the drug unattainable for a huge segment of the population.

If these prices are too high for a first-world country like the United States, the drug is therefore currently impractical as a preventative measure in the countries worst affected.

The Risk

Truvada can have serious side effects, including lactic acidosis (too much lactic acid in the blood), liver problems, kidney problems (including kidney failure), bone problems (including bone pain or bones getting soft or thin), and the worsening of hepatitis B infection. These can all be serious medical emergencies. The most common listed side effects include “diarrhea, nausea, tiredness, headache, dizziness, depression, problems sleeping, abnormal dreams, and rash.” In other words, this drug could be potentially life-threatening at worst, and deeply uncomfortable at best.

Many people also fear that the prevention drug is tempting fate—that gay men will suddenly start ditching condoms and lining up for unprotected sex. The fear is reminiscent of a popular argument in the sixties, when birth control was gaining popularity and people feared that women, freed from the fear of unwanted pregnancies, would begin engaging in promiscuous sex and amass countless STDs.

It turns out that this fear may not be completely unfounded.

A study published in Clinical Infectious Diseases found that the 40% of the 657 men in the San Francisco PrEP trial did use fewer condoms than they had prior to taking the pill and, though none contracted HIV, half became infected with syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia within a year. That said, 74% said that their number of sexual partners hadn’t changed, which means that rather than becoming more promiscuous, participants simply felt more safe and empowered having unprotected sex with their preexisting partners. This is a big deal in a community where sex has long carried the threat of real and life-threatening danger. Some men do indeed feel more liberated to have unprotected sex on PrEP—and feel entitled to this comfort as well, because for many gay men, it’s been a long time coming.

Some activists—notably Larry Kramer—are conflicted about downplaying the risks of unprotected sex. Some worry that the drug is a cop-out, charging huge fees for the promise of unprotected sex instead of teaching people about safe sex and responsible ownership of their bodies. With the HIV/AIDS rate currently rising at such a frightening rate, is it responsible to recommend that people spend tens of thousands of dollars on a brand new “miracle drug” (which has yet to stand the test of time) for the hope of risk-free sex, rather than simply using cheap, effective condoms?

Strides Made

We may have a long way to go, but treatment and prevention have come a long way since the dawn of the AIDS crisis. 15 million people are now on antiretroviral treatment, and new HIV infection rates have fallen by 35 percent. In 2000, less than 1% of people living with HIV in low and middle-income countries had access to treatment, which cost about $10,000 per year. Today, those prices have plummeted 99% to about $100 per year.

Such progress should inspire: if HIV treatment can become affordable, perhaps so too can preventative drugs. Truvada is by no means a cure-all. But we should definitely keep an open mind, and use Truvada alongside other tools in our AIDS-fighting Batman utility belts.