Chester Bennington is gone and I’ve been thinking all week about what it means for someone who kept so many people from committing suicide to have themselves committed suicide. It’s sort of unfathomable, in its way, like the way the world works is broken, like glue that has begun tearing bonds apart instead of holding them together.

But why should it be a surprise? Chester Bennington was mentally ill. He was able to channel his pain into the music of Linkin Park in a way that was poignant because it was so relatable. His music changed people’s lives. His songs extended lives, because people were able to see their own suffering in them and feel less alone.

When mental illness is channeled into productive energy, it is easy to dismiss the sickness that lurks behind it. But mental illness is serious—and, frequently, deadly. So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that someone like Bennington, a voice for the depressed and suicidal masses, became a fatality.

Now our newsfeeds are full of people who are either calling Bennington a selfish coward, tweeting the National Suicide Prevention Hotline numbers, or posting “don’t be afraid to reach out” Facebook statuses. Is there anyone who thinks these are effective ways to take care of potentially suicidal friends?

There are a lot of ways to more concretely support people struggling with mental illness. We can do so much better for each other, and we have to.

1. Mental Illness Can Be Fatal

Like physical illnesses, mental health issues can be serious and deadly, and they only stay invisible until they don’t. Mental illness can manifest physically in a variety of ways, including death by suicide.

Actually, the rates are kind of dismal. 44,193 people died by suicide last year in the United States, and the rates are rising every year. It is the tenth leading cause of death countrywide—before sepsis, before liver disease, before homicide. It is the second leading cause of death for young people between age 15 and 24.

Between 4 and 10% of schizophrenics die by suicide. Bipolar individuals are 15 times more likely to die by suicide than the general population, with about 50% (yes, half) attempting at least once. Eating disorders have the highest mortality rate of all mental illnesses, because patients die by suicide as well as from physical complications of their illness.

And that’s just suicide! Somewhere between a quarter and half of all fatal police encounters are estimated to involve untreated mental illness. That makes the risk of being killed during a police encounter 16 times higher for mentally ill individuals than other civilians.

This is why we have to do better at taking care of people who are suffering mentally, even if we cant see their pain. There are quite a lot of lives at stake.

2. Mental Illness Is Common

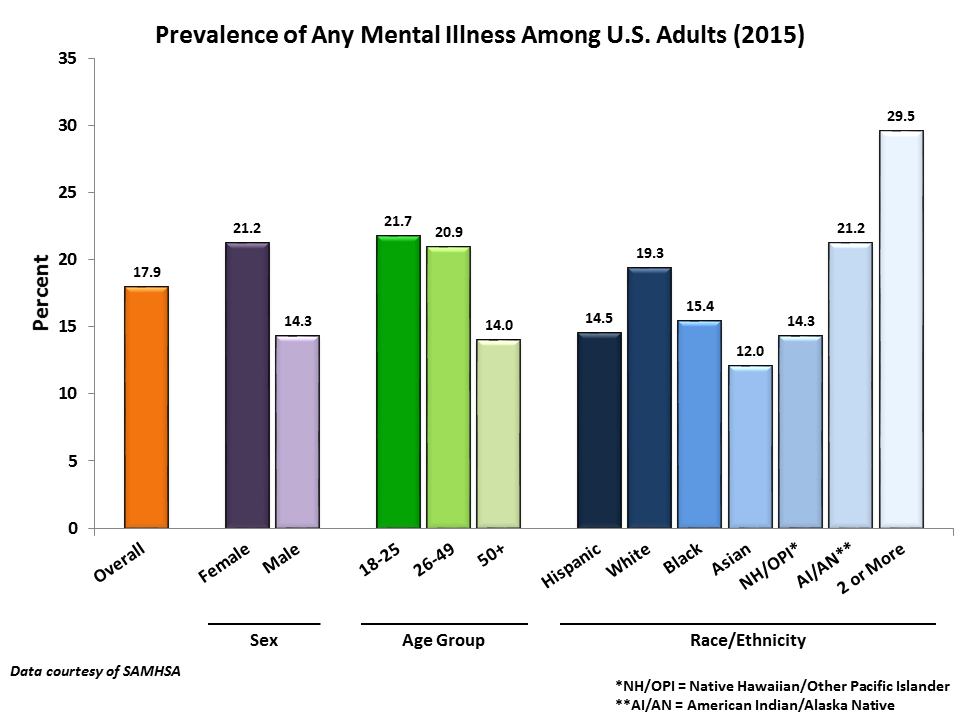

Mental illness isn’t just for rock stars and adolescent emo chicks. It’s a real issue that affects nearly 10 million adults in America, or about 4% of the population. And that’s just if you count mental illness that results in “serious functional impairment, which substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities.” In other words, the more visible kind of mental illness.

What about people who are still functional, but walking around on the edge? If you include them, the prevalence of mental illness in America shoots up to 43.4 million adults, or almost 18% of the population.

So even if you want to cut your compassion down to the raving screaming man on the D train, mental illness is still a crippling problem.

(PS: Without proper care, otherwise-functioning mentally ill people can turn into the raving screaming man on the D train…)

3. Stop Saying Suicide Is Selfish Or Cowardly

Suicidal people don’t kill themselves to be selfish. Often, they do so to stop being selfish. They see themselves as such a burden on those around them that they are certain the world would be better off without them. Some people can’t even imagine that their absence would even cause people pain or grief. In fact, if someone has struggled with agonizing mental illness for a long time, chances are they have been holding on every day specifically for their loved ones.

Sometimes, when people are so overwhelmed by mental anguish that they choose to take their own lives, they aren’t thinking rationally. They might be in a daze, or a psychotic state, far from reality. Of course the problems that suicide exists as an escape from are temporary –but they certainly don’t seem that way from the inside. They might genuinely think that suicide is their only option. And to do something as heavy, and as permanent, as kill yourself? That shit is scary. It’s brave, and people do it for selfless, if misguided, reasons.

It’s fine to talk about how tragic it must be for the loved ones left behind, and it’s even okay to be angry that someone’s gone from the world. But shaming dead people in this way only shows the living that they should be ashamed for having suicidal thoughts, which makes people less likely to reach out.

Instead, we can make a better effort to show our friends how loved and cherished they are while they are alive. Make sure your mentally ill friends know that they are not burdens. Make an effort to reach out to them and tell them how much you appreciate them. This is light years better than shaming people who did the best they could at the darkest time of their life.

4. Shut Up About “The Starving Kids In Africa”

I was twelve when I first encountered the stinging stigma of mental illness. After struggling through months of depression, I opened up to a friend about how I had been feeling. She told me that there were “starving kids in Africa” (oh, the many ways in which that racist trope emerges!) who would love to have the life I did, that I should feel grateful for the things I had, and that to feel depressed instead was selfish.

I didn’t feel any better—in fact, I felt way worse, because on top of being depressed, I felt ashamed for feeling so.

Pain, whether physical or mental, does not exist in relativity to that of others. This is why we don’t tell people with knife injuries to shut up because other people have ax wounds. On the other hand, pain can be relative to one’s own internal coping mechanisms, which is why a seemingly-small unpleasantness can be emotionally unbearable to someone who is already reached their mental limit. And also why some people are able to endure extremely painful situations that others can’t.

Instead of demanding that people who are depressed feel gratitude, what we can do is provide them with things to make them feel happy and grateful, no strings attached. Take her for a walk in the sunshine, bake him cookies, write a letter, play with puppies. Suggest volunteering at a soup kitchen, if you want, just save your jabs about how much food they have at home.

5. Yes, We’ve Tried Meditation.

Stop! Telling! People! To! Treat! Mental! Illness! With! Meditation! Or nature. Or exercise, or nutrition, or yoga. Just stop.

“Oh, you’re bipolar? Have you ever tried eating better?” sounds an awful lot like, “oh, stomach cancer? You should try soursop smoothies.” Do you seriously believe that mentally ill people haven’t tried all that shit yet? Do you also politely suggest that the overweight “just try dieting”?

Don’t get me wrong: exercise, yoga and healthy diets pump us full of good vibes and endorphins, and they absolutely do have positive effects on mental health. But when you tell a suicidal person that meditation and manifestation are better than medication, you are minimizing their illness and telling them that they should feel ashamed to need medicine, because meditating and manifesting should be good enough for everyone.

It’s great to talk about your own experiences (“when I’m sad, exercise really helps get it out of my system”) and swap coping skills. But presenting new-age alternatives to actual, medical help is counterproductive and potentially dangerous. You don’t know more about other people’s health than they and their doctors do. In general, people who are on medication should probably stay on their medication.

The stigma about being on medication for mental health is strong and frequently internalized. Taking a pill every day for your kidneys to work is one thing, but taking a pill every day for your personality – your very identity! – to work is quite another. It can be so challenging to overcome that stigma to seek help, and people frequently let a crisis build and break before they seek help at all, only to be told afterwords that their decision was silly.

It is true that medication doesn’t always work, that some medications are over-prescribed, and that some disorders are overdiagnosed. It’s also true that many kinds of depression and anxiety are learned rather than biological, which means they can often be non-medically treated, unlike disorders like bipolar or schizophrenia, for example.

But mood disorders can be extremely dangerous, and medical interventions can be necessary. Encourage people to seek therapy. Encourage them to explore all their options, even medical ones. And if someone tells you that medication works for them and makes them feel better, you should support them.

6. ”You Don’t Seem Mentally Ill”

Stop second-guessing other people’s mental health. We do this with physical illness too (see: women expressing pain) but it’s more pervasive with mental illness because it’s invisible.

Yesterday I told someone that I can be socially anxious sometimes. I was in a house full of relative strangers. My thoughts were racing a million miles a minute, second guessing every word that came out of my mouth. I felt stupider not speaking to anyone, like everyone noticed me sitting there strange and silent, so I told him almost as a confession. An excuse for how poorly I felt I was performing.

He narrowed his eyes and said, “Really? I don’t know; you don’t seem socially anxious at all. You’re talking to everyone!”

I had nothing to say. How do you explain that you’re exerting every ounce of mental energy to seem normal?

Does your illness only count when it’s visible? How anxious does one have to be to have anxiety? Does it only count if I don’t go out at all? Do I have to have a panic attack in the middle of the room? Sit, miserable, in a corner?

This skepticism leaves people feeling that they have to “prove” their illness somehow. If what you mean to say is, “wow, you cope so well, I wouldn’t even have noticed!” try saying that instead. Instead of being a skeptical judgment, your observation then turns into a compliment for someone to be proud of!

7. Show Up

Many people considering suicide right now are not going to reach out to you. They aren’t going to read your Facebook status and think it’s for them, and they definitely aren’t going to call the suicide hotline you tweeted. It’s not enough.

Learn the symptoms of depression and signs of impending suicide. Pay attention to your loved ones. Send an extra text, make an extra phone call. Don’t take it personally if someone doesn’t answer. Keep pushing.

People struggling with their mental health often have extra trouble taking care of themselves and accomplishing basic tasks. Cook them dinner, or take them out. Come over and help clean their house or do the dishes. Offer to take the dog for a walk. Make sure they’ve washed their hair recently. Help them with that paper, with their taxes, sorting their mail. They will not ask. You have to go the extra mile here.

Make sure people know you love them. Remind them of how valuable they are to you; be specific about what they mean to you and others. Tell them again. Remove firearms and other deadly weapons from their homes. Don’t just suggest therapy, find out what kind of insurance they have and refer them somewhere that they’ll be covered. Offer to go with them to an appointment. If they don’t want you to come, remind them to go.

Yes, it is more difficult to maintain a relationship with someone who is struggling with mental illness. You will likely have to try a little harder than you do with your other friends. But it will mean the world to them to know they mean the world to you. And it could be the difference between life and death.

Thanks for your art, Chester Bennington. For so many of us, it made the difference.

In case you didn’t realize, the word “Solow” on your site is spelled incorrectly. I had similar issues on my website which hurt my credibility until someone pointed it out and I discovered some of the services like SpellHelper.com or SpellingCheck.com which help with these type of issues.