The New York Times published an article by Katharine Q. Seelye today titled “As Heroin Use by Whites Soars, Parents Urge Gentler Drug War.” Much of the meat is in the title: white people are suddenly doing a ton of heroin, and so drug abuse should be decriminalized. [Edit: The article’s title has since been changed to “In Heroin Crisis, White Families Seek Gentler War On Drugs.”]

It’s a beautiful sentiment, at its heart. Addiction is psychological, in many cases as much as or more than it is physiological, a mental illness that can prompt criminal behavior in people who are not otherwise criminals. If you treat the disease you can treat the crime. But the War on Drugs has been reversing this process, spending millions every year to incarcerate people for drug crimes while completely de-funding life-saving needle exchange programs. More than half of the federal prison population are there for drug crimes. And even though white people do and sell as many drugs as people of color, people of color are disproportionately arrested and imprisoned for drug crimes.

Now that addiction is a middle-class-white-people problem, too, cops like Eric Adams, a white former undercover narcotics detective, are quoted in the New York Times saying “The way I look at addiction now is completely different,” and that “I can’t tell you what changed inside of me, but these are people and they have a purpose in life and we can’t as law enforcement look at them any other way. They are committing crimes to feed their addiction, plain and simple. They need help.”

It seems clear, though, what has changed: color. Addiction has now been made visible by whiteness. Sympathy and lenience for white addicts isn’t a new thing, either, there’s just enough of them now that white people are starting to call their local representatives and PTAs. I was a young addict that got out with my life and without a record. I wonder all the time what my life would have been like if I wasn’t white.

Addicts and Troublemakers

I fought an all-consuming battle with mental health and addiction throughout nearly all of my adolescent and teenage years. The battle was not subtle; it did not stay neatly contained in my mind and bedroom. No. It was a conspicuous tornado that frequently turned me into an unpleasant, angry black hole of trouble.

I was a self-destructive kid with a bad attitude and something to prove. There were never any consequences. I swore at authority figures. I fought and stole, ran away for whole weekends, skipped school, broke probation, trespassed, vandalized, ran from cops. I’ve been tackled by a cop while trying to run from him and simply released; unharmed, uncharged. I was picked up by cops over and over and over again, only to wait at the police station for my livid mother to show up. I was once driven home to my mother in the middle of the night to “protect me” from the drugs found on the other people I was with (my friends, our drugs) while everyone else in the car was arrested and booked. I was underage, and they weren’t, which probably had something to do with it. But in hindsight it all feels a little too lucky.

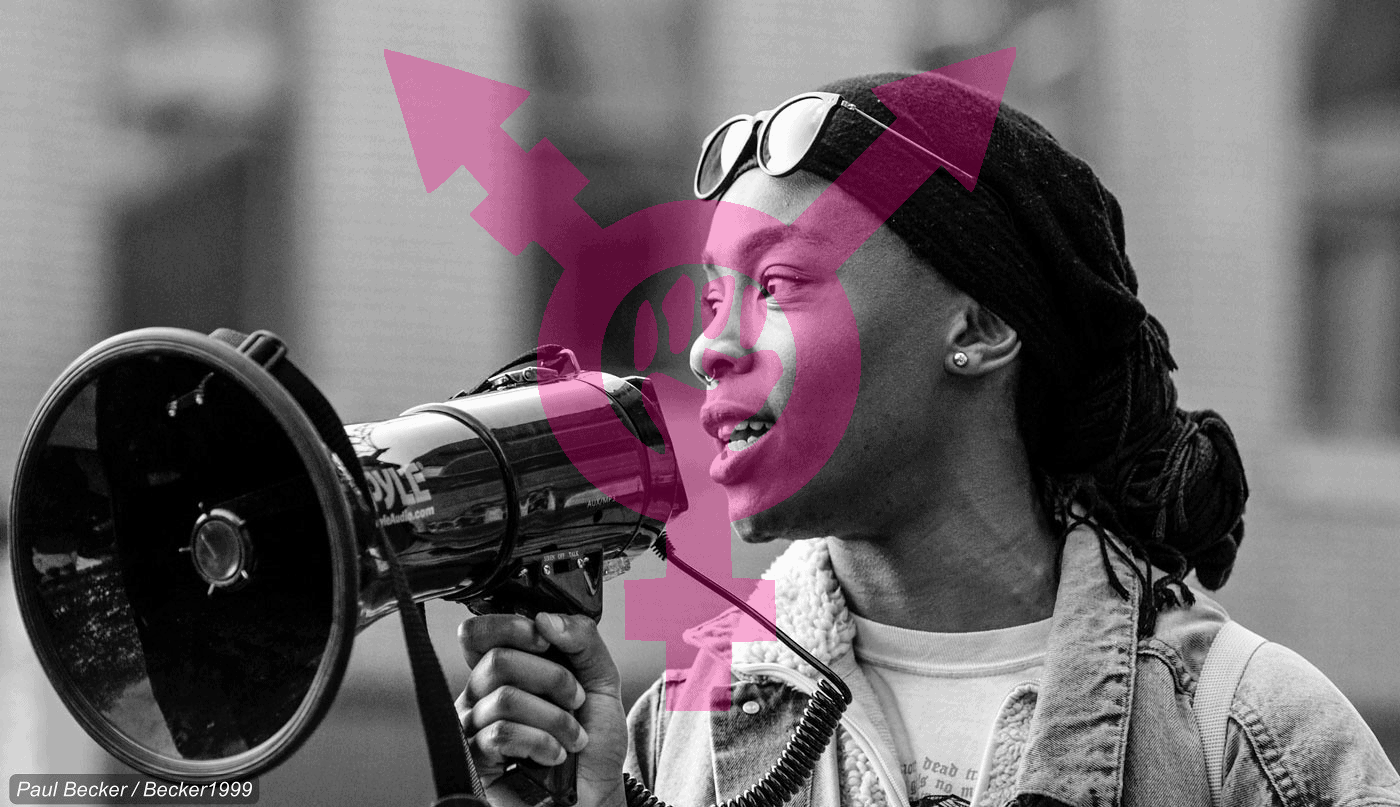

This afternoon, just hours before I read the New York Times article, I was talking to someone about that poor teenage girl in Spring Valley High School who was thrown across the room and arrested for quietly refusing to put her phone away or get up. Though nobody seems to care about her backstory beyond what she must have done to “deserve” this violence, it’s come out that she’s currently living in foster care, so she’s got some stuff going on beyond the basic difficulties of just being a teenager. I had read comments that blamed the girl’s “disrespectful attitude” for the cop’s brutality.

My skin bristled with goosebumps, remembering myself at her age: a depressed and angsty teenager who sullenly refused to speak or cooperate, an angry addict who argued with authority. At first I said, “how lucky that never happened to me.”

Then, I corrected myself: “how fundamentally lucky to have gone through all that as a white girl.” Because if my experiences as a troubled white kid with cops and drugs looked anything like the experiences of similar or even untroubled teenagers of color, I might not have lived through it at all, and definitely wouldn’t have caught the breaks that I did.

Selective Vision

I raised hell and was considered sick or troubled the whole time, despite and beyond any criminal or destructive or violent choice I made. Just about every authority figure I encountered wanted to help me. I was always a “good kid” that just “got caught up in the wrong thing.” People rarely assumed that I was, at heart, a criminal.

Even within the scope of the more-forgiving protocol for minors, I got probation and support groups instead of detention centers or violence every single time. What makes that consistent lenience so noteworthy is that over the course of several long years, there were so many times my luck could have played out differently. But it never, ever did. I am certain that white privilege played a huge part in keeping me alive. The white supremacy that sustains that privilege is more than happy to let black and brown people die for less.

I do celebrate the new approach; it’s enough to worry about your loved one overdosing without fearing that they’ll end up in prison or shot to death. Addicts are sick people that need help and a whole network of support and mental health treatment and love and detox and halfway houses and patience and safety and second chances. But the racist implications of this timeline cannot be ignored. Letting white folks slide on drug crimes is nothing new. And our nation has proven more than willing to lock up, let die, ignore, or dismiss generations of black and brown addicts as bums and criminals and irresponsible thugs in the past. That’s been protocol for a century. More.

Let us move, please, away from mass incarceration of drug users. But if addicts only become people who need help when they’re white, I weep for the millions who go every day unseen and assaulted, ignored and imprisoned, for wrestling with the same demons.